Your Health Unlocked Episodes

041: Menopause Must-Knows in 2024 with the National Menopause Foundation

March 21, 2024

---

Consumer Health Info

Publication Date: November 30, 2017

By: NWHN Staff

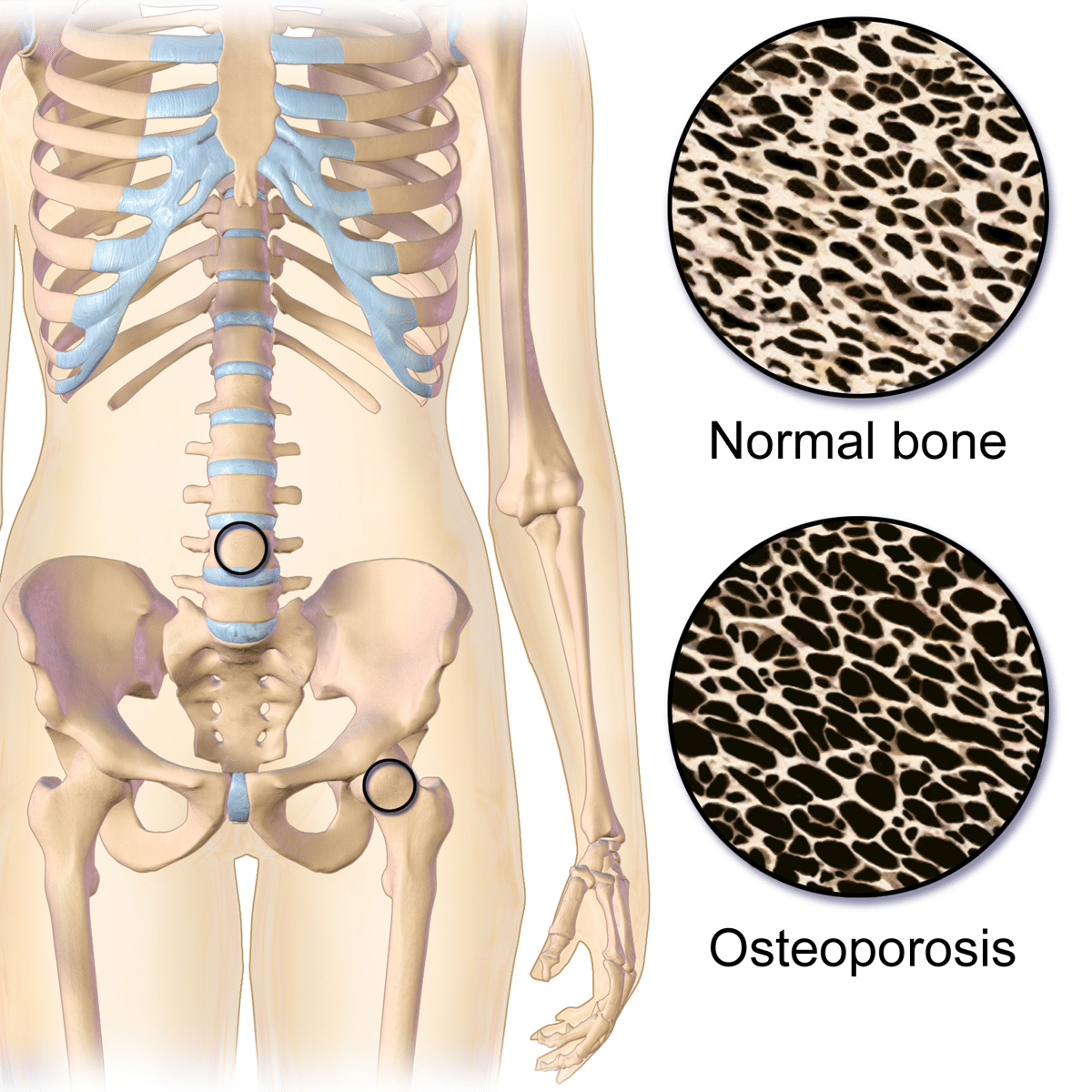

Osteoporosis is a condition that causes bones to become fragile and susceptible to breaking. Fractures, and the consequent pain and disability they cause, can seriously affect a person’s health and quality of life. Women are more likely to develop osteoporosis than men, and some women experience fractures that could have been prevented if their osteoporosis had been detected and treated. However, not every woman who is warned about bone thinning needs to be worried.

Osteoporosis, a term which literally means porous bone, is a deviation from the natural process of bone remodeling whereby bones become fragile and more susceptible to fracture. This happens when the microarchitecture – or “scaffolding” – of a bone becomes weaker. Often, osteoporosis is defined as a disease of low bone density. The NWHN rejects this definition – while bone density is one contributing factor to bone strength, reduced bone density is just one of many bone characteristics that can contribute to fracture. Cell type, shape, and arrangement are just a few examples of other characteristics that also influence bone strength. To adequately address the underlying causes of fracture, we must think about bone weakness as more than just bone density.

There are approximately 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures in the United States each year. Preventing hip and vertebral (spine) fractures is an important goal in women’s health. Hip fractures are especially debilitating, often requiring hospitalization and surgical treatment. It can take months or years to fully recover. Acute vertebral (spinal) fractures can be very painful, but more often they are tiny and painless. These asymptomatic vertebral fractures are often undiagnosed until detected by X-rays done for other reasons.

There are several risk factors for fracture that are independent of bone density. The three most important risk factors are age, sex, and prior fracture history. Postmenopausal women are at highest risk, especially those who have previously experienced a fracture. Age is an especially important risk factor for people who didn’t build up their bones to their fullest potential as a child and young adult. Removing a woman’s ovaries increases the risk of developing osteoporosis, as do some medications including certain anti-seizure drugs called benzodiazepines and high dose steroids. Lifestyle choices like smoking, high caffeine intake, or high alcohol intake can increase the risk of having a fracture. So can inactivity – studies have shown that adults who spend more time walking and on their feet are less likely to fracture than sedentary adults.

The NHWN believes that the routine practice of screening for osteoporosis using imperfect technology should be balanced by increased awareness of the shortcomings of these techniques. Efforts should be focused on encouraging healthy bones and preventing fractures, not treating women with slight changes in bone density who are otherwise at low risk of fracturing. Better osteoporosis screening tools are badly needed, and research is currently underway on several different options. For more information on these emerging technologies, visit our osteoporosis innovation consumer health information. This is intended to help women understand what is osteoporosis, what screening methods are available right now, and what the NWHN recommends for osteoporosis screening.

Pharmaceutical companies pushed for the adoption of a particular screening tool called a DEXA scan, which measures bone mineral density in the hip or spine. DEXA scans are safe and pose no health risk. However, their methodology almost guarantees that the scan will reveal bone loss. The test produces a number called a T score, which shows how far away a woman’s bone density is from that of a healthy young woman. The results range from normal (T score of -1 or greater) to osteopenia (-1 through -2.5) to osteoporosis (-2.5 or smaller). Since everyone loses bone density with age, the test is almost guaranteed to show some bone loss. Additionally, it is important to remember that bone density is only a reflection of bone quantity, not quality. It is entirely possible to have weak but dense bones or vice versa. In order to correctly predict women at risk of fracture, the test casts the net wide – falsely identifying many women who need not be worried even if they do have bone density loss.

DEXA scans should be interpreted with caution. While they can predict fracture risk in the short-term, a scan taken at age 45 generally has no value for predicting what may occur when the woman is 70 or 80 (when debilitating fractures are most likely to occur). Additionally, specialists have observed that small changes in positioning of hip and spine for BMD studies result in large changes in T scores. There is also variation between machines, even from the same manufacturer. We recommend that women getting repeat scans have them done on the same machine, if possible.

Questions also exist about the value of DEXA screening for women of color. African American and Latina women typically have denser bones and lower fracture rates than White women, while Asian American women typically have thinner bones, but also have lower fracture rates than White women. The original DEXA studies did not include any women of color and far fewer studies have been done on women of color compared to white women. This leaves us with less information about normal bone density scores for women of color, how bone density differs between different racial or ethnic backgrounds, and whether DEXA scans are effective at predicting fracture risk for women of color. NWHN believes that research is needed on both osteoporosis and the use of DEXA scans in women of color, and until such research has been conducted we recommend that women of color approach screening with even more caution.

The United States Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that adults get their first DEXA scan at age 65 unless they are at particularly high risk of fracture due to unusual factors like long-term steroid use. The NWHN endorses this recommendation with the caveat that DEXA results should be considered in conjunction with other risk factors when making treatment decisions.

USPSTF does not make recommendations about when to get subsequent testing after the baseline scan at age 65. Studies indicate that one can safely wait as long as ten to fifteen years before returning for a second test if the baseline result reveals “normal” bone density (a T score of -1 or greater). If the baseline DEXA test indicates osteopenia (-1 to -2.5), interpret this as a reminder to take steps to promote good bone health. Those with a DEXA result of osteopenia can return for a test within two to five years, depending on the severity of bone loss. If diagnosed with osteoporosis (-2.5 or less), an individual will need to consider, in consultation with a provider, how to address this diagnosis. The interval of repeat scanning will depend on the treatment plan selected. Treatment decisions are both personal and complex, and not all drugs confer the same level of benefit. To be prepared for this conversation, check out our content on osteoporosis treatments.

There have been attempts to make DEXA results better at predicting who is likely to fracture by incorporating clinical risk factors. Part of the reason DEXA is used routinely is that quantitative benchmarks make treatment decisions easier for doctors and patients. Several osteoporosis algorithms have been developed to use complex clinical data, like family history, diet, and prior fracture, and DEXA results to produce a more accurate numerical estimate of how likely a woman is to fracture within the next ten years. FRAX™ is the most widely used of these algorithms. However, how much importance the FRAX™ algorithm gives to each risk factor is not public information – meaning the algorithm could still be relying too heavily on DEXA scores. For more information on the FRAX™ algorithm, see our Innovations in Osteoporosis consumer health information.

Postmenopausal women are at the highest risk, especially those who have previously experienced a fracture. Age is an especially important risk factor for people who didn’t build up their bones to their fullest potential as a child and young adult. Removing a woman’s ovaries increases the risk of developing osteoporosis, as do some medications including certain anti-seizure drugs called benzodiazepines and high dose steroids. Lifestyle choices like smoking, high caffeine intake, or high alcohol intake can increase the risk of having a fracture. So can inactivity – studies have shown that adults who spend more time walking and on their feet are less likely to fracture than sedentary adults.

Postmenopausal women are at the highest risk, especially those who have previously experienced a fracture. Age is an especially important risk factor for people who didn’t build up their bones to their fullest potential as a child and young adult. Removing a woman’s ovaries increases the risk of developing osteoporosis, as do some medications including certain anti-seizure drugs called benzodiazepines and high dose steroids. Lifestyle choices like smoking, high caffeine intake, or high alcohol intake can increase the risk of having a fracture. So can inactivity – studies have shown that adults who spend more time walking and on their feet are less likely to fracture than sedentary adults.

In the 1980s, women’s health advocates were concerned that the medical community had overlooked the effect of bone fractures on older women’s quality of life. We advocated for change – but today the pendulum has swung to the other extreme. For decades, pharmaceutical companies conducted aggressive advertising campaigns, seeding fear of the “silent killer” osteoporosis. They used promotional campaigns to convince women and health care providers that osteoporosis is a threat to middle-aged women as well as older women. Independent medical experts now recommend that women wait until age 65 to be screened for osteoporosis, but these earlier campaigns convinced providers that women in their 40s and 50s needed screening. The adoption of these early screening practices led women and their physicians to falsely conflate natural bone loss with pathological risk. All of this was done so companies could bolster drug sales and reap greater profits.

Throughout life, our bones are constantly remodeling. Natural processes break down bones and build them up at a microscopic level. This natural process is influenced by age – children and young adults build more bone than they break down. Bone mass peaks around age 30 and then declines – women tend to lose bone most rapidly during menopause. Age is not the only factor that influences our bones – they also remodel in response to our activity level. Individuals who do weight bearing exercise consistently develop greater bone mass after several months, while those who remain sedentary for long periods of time lose bone mass.

Drug companies have had a heavy hand in shaping how we screen for osteoporosis, introducing screening designed to promote overtreatment and pushing it towards younger and younger women. The NWHN encourages women under age 65 to reject bone density screening unless they have unusual circumstances that increase their risk. Additionally, we support integrating DEXA with consideration of other risk factors when making treatment decisions, rather than relying on DEXA results alone.