Health Info, Policy Updates

10.14.24 Voter Empowerment Alert

October 13, 2024

Check out Vote 411's Healthy Voter Checklist here. Get more free voting tips and resources at our Voting HQ Page.

Consumer Health Info, Deep Dive Articles, Health Info

Publication Date: March 28, 2023

By: Emily Morson (MS), Neuroscientist and NWHN Contributor

In the early 1900s, four American women sued doctors for performing medical operations on them, either against their will or without asking them for consent. The courts ruled that these women had the right to decide what happened to their own bodies. These court decisions laid the foundations for the legal principle that humans must give informed consent to get medical treatment or participate in research.

What do unwanted surgical operations in the 1900s have to do with research studies today?

It’s a long, colorful story.

In 1905, Mrs. Anna Mohr sued Dr. Williams, a surgeon and ear specialist in St. Paul, Minnesota, for assault and battery. She sued for $20,000 in damages, saying he had damaged her hearing while operating without her consent. The case went before the Minnesota Supreme Court.

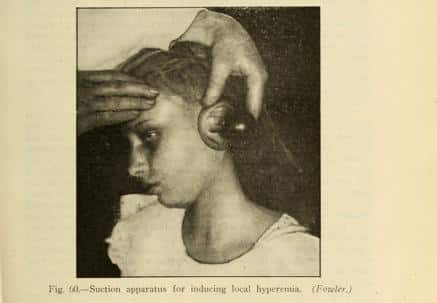

Mrs. Mohr went to Dr. Williams concerned about “trouble” with her right ear. (It’s not clear whether she was experiencing pain, hearing loss, or both). Examining her right ear, Dr. Williams found three problems: a big hole in her eardrum, a large polyp in her middle ear, and diseased ossicles (the small bones in her middle ear).

He also tried to examine her left ear but couldn’t do so thoroughly because there was a “foreign substance” in it. Mrs. Mohr was not told there was any disease in her left ear.

Dr. Williams recommended surgery on Mrs. Mohr’s right ear to remove the damaged and diseased areas. Despite her fear of anesthesia, she agreed.

Just before starting the surgery, while Mohr was unconscious, Dr. Williams realized her ears were in a different condition than he’d thought. Her right ear was “less serious” than he’d expected, so he decided it didn’t require surgery. Meanwhile, her left ear was in a much more serious condition than her right. It had a hole in the eardrum and a diseased, dead bone in the middle ear. Dr. Williams decided to operate on Mrs. Mohr’s left ear instead of her right.

Instead of waking Mrs. Mohr to tell her these discoveries and ask for her consent to the change in plans, Dr. Williams performed the surgery while Mrs. Mohr was unconscious. Not surprisingly, she was furious.

Dr. Williams argued in court that Mrs. Mohr had already agreed to surgery on one ear, so she had implicitly agreed to surgery on the other. She disagreed.

The court concluded, “an operation that is performed without the consent of the patient is wrongful,” except in a life-threatening situation, which was not valid for Mrs. Mohr. “Consent should have been obtained,” so the operation “was unlawful.” Mrs. Mohr was awarded over $14,000 in damages.

Her case is now used in American law schools to teach students about consent.

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma case Rolander v Strain in 1913 extended the decision in Mrs. Mohr’s case to a similar situation. Mrs. Rolander sued her surgeon, Dr. Strain, for assault and battery for removing one of her foot bones against her wishes.

Mrs. Rolander stepped on a nail near her workplace, the Pioneer Telephone Telegraph Company. It pierced her right big toe, which became infected. When the wound didn’t heal, she went to Dr. Strain, a surgeon who owned a sanitarium in Oklahoma City.

The surgeon recommended making an incision in her foot to drain and clean the infected joint. She agreed to the operation. She also told him she didn’t want any bones removed.

However, while doing the surgery, Dr. Strain removed a bone from her right foot. He said it covered and blocked the infected joint, so to drain the joint as he and Mrs. Rolander had agreed, he had to remove it. Instead of discussing the problem, he went against her stated wishes.

Mrs. Rolander argued similarly to Mrs. Mohr: the surgeon obtained consent for one operation and then did a different one. In Mrs. Mohr’s case, the procedure was the same, and the organ was different; in Rolander’s case, the organ was the same, and the procedure was different.

Mrs. Rolander argued that it didn’t matter whether the surgeon intended to injure her; it was unlawful simply because she didn’t consent. The court agreed with her.

“In a civil action by a patient against a surgeon for assault and battery, it is not necessary to show that the surgeon intended, by the act complained of, to injure the patient. …Consent of the patient…is necessary to authorize a physician to perform a surgical operation upon the body of the patient. An operation without such consent is wrongful and unlawful, and renders the surgeon liable in damages.”

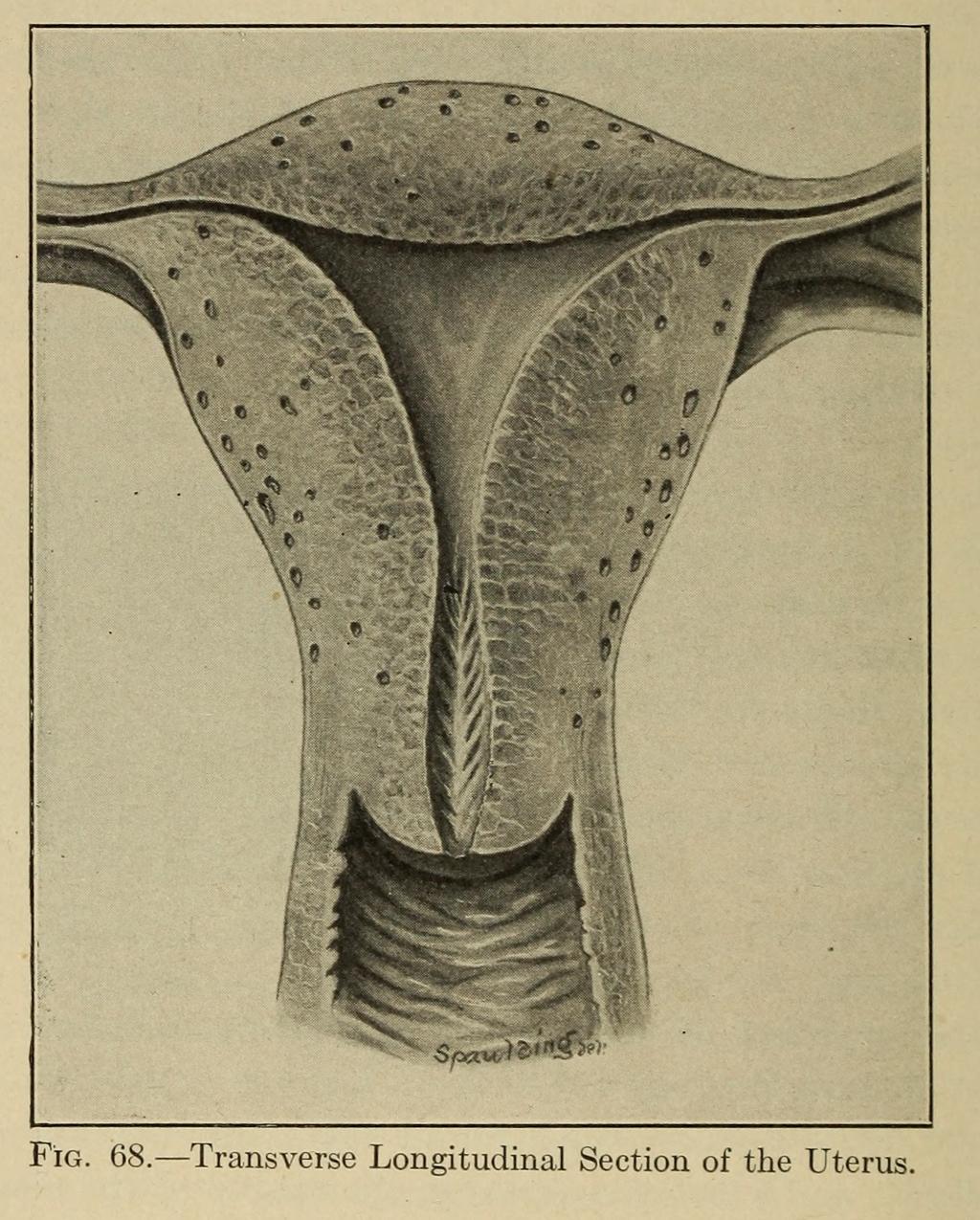

In 1906, an Illinois appellate court awarded damages to Mrs. Parmelia J. Davis because her ovaries and uterus were removed without her, or a proxy’s, consent.

Mrs. Davis was a 40-year-old woman with epilepsy. For 15 years, she had increasingly frequent seizures that left her “weak in body and dazed and uncertain in mind” for several hours afterward.

In 1896, she went to a Chicago sanitarium. There, Dr. Edwin H. Pratt found her uterus was damaged, and her lower rectum was diseased. He performed surgery to treat these conditions.

Her seizures continued; epilepsy is a condition of the brain, not the pelvic organs. A few months later, Mr. Davis asked his brother to take her back to the sanitarium. The next day, the surgeon removed her ovaries and uterus.

The court clearly understood that Mrs. Davis did not consent to her organs being removed. Incredibly, the doctor admitted to “deliberately and calmly deceiving the woman; that is, I did not tell her the whole truth.”

However, because Mrs. Davis had epilepsy, she was considered insane and therefore unable to consent. Thus, her husband must consent on her behalf. Even by the norms of the day, the judgment that she couldn’t make rational decisions was questionable. Those who knew her said that her state of mind was normal, except for a short period immediately after her seizures.

The court considered whether Mrs. Davis’s husband had given consent. He argued that he and his wife had given consent to the first surgery, but that didn’t mean they consented to the second. The surgeon told him to return her for “the finishing work,” not explaining what that meant. The husband did not know what surgery would be done but gave consent for it anyway. The doctor says Mr. Davis only “made the request” to “do as little as possible,” which was not honored.

The court agreed that Mr. Davis did not agree to the second operation, so Mrs. Davis’s organs should not have been removed.

Although the court ruled in her favor, Mrs. Davis’s story did not end happily. She was said to have gradually declined mentally. In 1898, she was judged insane and sent to the State asylum at Kankakee. She was not called as a witness to a trial about her own body. She did not live long enough to see her case become important for establishing patients’ right to self-determination.

The court said something very important:

“The consent of the patient should be a prerequisite to a surgical operation where he is in possession of his mental faculties and well enough to consult about his condition without dangerous consequences to his health, and where no emergency exists making it impracticable to confer with him or requiring immediate action for the preservation of life or limb.”

In other words, except in life-threatening emergencies, surgery requires either the patient’s or a proxy’s consent.

The Court expressed people’s right to make decisions about their own bodies in stirring words:

“…Under a free government at least, the citizen’s first and greatest right, which underlies all others-the fight to the inviolability of his person, in other words, his right to himself.”

The Court found Mr. Davis did not consent in part because he was uninformed. The surgeon had deceived the patient and withheld information from her proxy. The idea that consent to treatment must be based on a full understanding of what will happen underlies the modern concept of “informed consent” to treatment and research.

In 1908, Mary Schloendorff said she did not want to undergo surgery, but was given a hysterectomy to remove a fibroid tumor without her consent.

Mary Schloendorff went to New York Hospital for “some disorder of the stomach.” Dr. Bartlett, who worked there, found a fibroid tumor and consulted another surgeon, who recommended surgery. Schloendorff refused surgery but allowed the doctor to examine her under anesthesia. While she was unconscious, Dr. Bartlett performed surgery to remove the tumor.

Afterward, Schloendorff developed gangrene in her left arm, and several fingers had to be amputated. She sued New York Hospital in 1914.

The court agreed that operating against a patient’s will was battery, but the doctors were responsible, not the hospital. Judge Benjamin Cardozo stated the principle of consent in the strongest terms yet, referring to Mrs. Mohr’s and Mrs. Davis’s cases:

“Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault, for which he is liable in damages.”

This principle became precedent.

After World War II, the world was horrified by Nazi researchers’ crimes against humanity. Americans decided to set up laws to prevent similar abuses at home. They referred to these four women’s cases in developing a new, legally binding concept: “informed consent.”

We saw the need to consent to a medical procedure in all four cases. In Mrs. Davis’s case, we saw that real consent requires being fully and truthfully informed. In a 1957 California appellate court case, these two ideas were combined under the name “informed consent.”

The case enumerated specific things people must know to give “informed consent” to a medical treatment. These include the treatment’s duration, purpose, methods, and likely positive and negative consequences.

“Informed consent” is also required for research studies involving humans. Since 1957, the United States government has passed several laws that set up the current human research regulations. All these regulations assume participants must give informed consent and define and protect that right.

Today, if you volunteer for a clinical research study, you will be told:

You are also given contact information to complain or report abuses.

You can thank four women – Mrs. Mohr, Mrs. Davis, Mrs. Rolander, and Mrs. Schloendorff. Before women even had the right to vote, they called on the courts to protect their right to decide what happened to their bodies. Their cases set precedents for laws that protect patients and research participants today.

The suffering of these women was unimportant to their doctors and society at large, while their wishes and complaints were not taken seriously. The extent of these problems seems shocking today. For example, Mrs. Davis and Mary Schloendorff waited to seek treatment for an amount of time that might be hard to imagine now. However, women and their pain are still devalued in subtler ways today.

Mrs. Davis lived with increasingly frequent epileptic seizures for 15 years without seeking treatment. She waited so long because she was “able to perform her household duties” and bear three children despite her symptoms. Her own suffering, apparently, wasn’t a good enough reason.

Similarly, Mary Schloendorff waited 2 months for an infected wound to heal before seeking treatment.

People still delay seeking treatment today for reasons ranging from high costs, the fear of being shamed or misunderstood, discomfort with medical staff or physical examinations, and more. During the lockdowns of COVID-19, for example, 41% of adults in the U.S. reported delaying or avoiding medical care due to COVID-19 concerns. Still, others delay care for fear of being shamed or talked down to by culturally incompetent medical staff.

In Mohr v Williams, the Court’s word choices show bias in favor of Dr. Williams and doubt about Mrs. Anna Mohr’s claims. For example, one of the “facts” of the case is the subjective judgment that Williams is an “excellent” doctor and ear specialist and a “physician of standing and character.” The court also listed as “fact” that the surgery was “in every way successfully and skillfully performed.” Mrs. Mohr only “claimed” that her hearing was impaired, a wording that casts doubt on her testimony.

The court rejected Mrs. Mohr’s claim that her hearing was impaired after the surgery and that her hearing loss was relevant to the case! That’s because “the evidence fairly shows that the operation complained of was skillfully performed and of a generally beneficial nature.” The court only cared whether Mrs. Mohr had consented to the surgery.

In other words, it dismissed her hearing loss as either nonexistent or unimportant.

Amazingly, the court ruled in Mrs. Mohr’s favor despite this bias.

Similarly, in Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, the court’s wording shows a bias to trust medical professionals over patients. The Court called Mary’s testimony “improbable,” emphasizing that it was “contradicted by Dr. Stimson and Dr. Bartlett, as well as by many of the attendant nurses.”

We know that implicit bias exists in medical settings to this day. Some common unconscious biases observed in modern health care settings include:

The New York Court of Appeals details how Mary Schloendorff tried to express her wish not to receive surgery. She communicated her message to a nurse in the middle of the night, and it was interpreted as a request for reassurance from the nurse rather than a decision to be communicated to the surgeon. In short, Mary spoke to the wrong people at the wrong time. The court said that any reasonable person would treat her wishes like the nurses did. The court’s opinion does not explain who Schloendorff was supposed to tell, when, or how she was supposed to know how to navigate the hospital system.

Mary Schloendorff’s difficulty in making her wishes known may feel all too familiar to many women today. The medical system has only gotten more complex since 1908, and patients have even more barriers to overcome. We get questions from our supporters daily about how to access different types of care, how to make doctors listen, and what the latest federal policy rollouts like insulin price caps or draconian abortion restrictions mean for them in their daily lives. That’s why we’re committed to bringing you the best consumer health information and keeping you updated with deep-dive articles like this. If you’d like us to cover something specific in another article, send your request to [email protected].

Images sourced from the Library of Congress