Your Health Unlocked Episodes

050: Voting in 2024 – Why it Matters and How to Do It

July 25, 2024

---

Deep Dive Articles

Publication Date: October 31, 2023

By: Rachel Grimsley, (RN, BSN, MSN) Volunteer Health Officer

Margaret Jones: The Woman with the Malignant Touch Tituba: The First Accused of the Salem Witch Trials Grace Sherwood: The Witch of Pungo Why Were Midwives and Healers Targeted as Witches? The Link to Modern Day

Margaret Jones was the first person executed by hanging for witchcraft in Boston, Massachusetts [2]. Not much information is available surrounding her case aside from diary entries by Governor John Winthrop and Reverend John Hale (The same Reverend Hale who brought the Salem Witch Trials to an end when his wife was accused) [2]. Margaret Jones was known as a healer and midwife in her town. She would practice “physic”, or making medicines, and was known to have prophetic visions and knowledge of speeches or church sermons that she couldn’t have known [2]. In 1648,

Margaret was accused of witchcraft by her patients. They claimed that she had a malignant touch, which caused deafness, vomiting, or other pains or sickness when she touched others [2]. Despite saying her medicines were simple liquors made of anise seed, they were reported to have “extraordinary violent effects” by those who took them [2]. Her patients claimed that Margaret told them they would never be healed if they didn’t take her medicines, and their diseases and hurts continued and baffled local physicians and surgeons [5]. Margaret and her husband were arrested for witchcraft, and Margaret was watched for 24 hours to see if she was a witch.

A year before Margaret’s arrest, the book, “The Discovery of Witches,” was published as a witch-hunting manual, which said to watch a witch for 24 hours to see if the witch’s imp would come to feed [2]. The officer watching her claimed he saw a child in her cell that ran from Margarets’ arms into another room and vanished [2]. Others claim they also saw this child, leading to Margarets’ conviction and sentencing [2]. To further her guilt, Governor Winthrop wrote that her behavior at her trial was “very intemperate, lying notoriously, and railing upon the jury and witnesses” [2].

On June 15th, 1648, Margaret was hanged at Gallow’s Hill at Boston Neck [2]. Within the hour of her hanging, Governor Winthrop wrote that a large storm hit Connecticut, blowing down many trees [2]. This was further proof to the town’s folk that Margaret was, indeed, a witch. Her husband was not convicted, but the blight of being the husband of a convicted witch was enough to ruin his reputation. He was even thrown off a ship headed to Barbados for purportedly causing it to sway back and forth, which steadied after he was removed [2].

Tituba was a woman that was likely of Native American ancestry that was enslaved and taken from Barbados to Salem, Massachusetts. Her enslaver was minister Samuel Parris [5]. She was the first of three women accused in the infamous Salem Witch Hunts beginning in March 1692 [5]. The young girls that exhibited the first signs of witchcraft were the daughter and niece of the minister, and Tituba was close to them both [1]. The girls were dabbling in a dangerous and forbidden practice: fortune telling [1]. They dropped egg whites into a glass of water, expecting the egg whites to show their future husbands and their lives, instead, it showed the shape of a coffin, sending them into a hysterical fit of crying, babbling, and even barking like dogs [1].

Tituba being of Native ancestry, was thought to be a cunning woman, or someone who used white magic and could recognize a witch’s magic, as Puritans believed that Native Americans could recognize evidence of witchcraft and the work of the devil [5]. The mother of one of the girls asked Tituba to bake a witch-cake. Witch-cakes were made with rye bread and the urine of the victim, then fed to a dog who would bark out the name of the witch [5]. Minister Parris was furious when he discovered this and condemned the use of white magic saying they had “gone to the devil for help against the devil” [5].

Tituba’s arrest and interrogation is thought to have sparked the hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials themselves. While the other two women, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, denied practicing witchcraft, Tituba did not [1]. When asked who hurt the girls, she replied, “The devil came to me and bid me serve him” [7]. When it was demanded who tortured the girls, she replied, “the devil for all I know” and began to describe him [7]. She said a tall, white-haired man in a dark coat appeared and arrived with his accomplices from Boston, a hog, a great black dog, a red rat, a black rat, a yellow bird, and a hairy creature that walked on two legs [1]. She was able to provide a story for any question asked by the court. From her sensational confession, she described the devil’s book with names of witches, creatures she couldn’t describe other than having “wings and two legs, and a head like a woman,” and that she had signed a pact with the devil, in blood [7].

After days of questioning and delivering the confession of the century, Tituba cried out that she was blinded by the devil and could not see [7]. The months following had the colonists frozen in their tracks, seeing strange beasts and shape shifters and suspecting the devil in every shadow.

Eventually, Tituba did take back her confessions, saying she was bullied by Minister Parris, but the hysteria had spread and between 144 and 185 people were accused of witchcraft, and 19 were hanged by September of 1692 [7]. Despite recanting her confession, she served over 13 months in jail. Minister Parris refused to pay her bail, but an anonymous person did, and Tituba went free, disappearing into history [1].

Statue of Grace Sherwood in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Image sourced from Atlas Obscura, donated by user https://www.atlasobscura.com/users/obfuscott

Grace Sherwood was born in 1660 in Colonial Virginia. From descriptions in historical documents, she was tall, attractive, stubborn, and outspoken [3]. Blessed with a loving husband and three sons, Grace was living her best life on their farm. With all her happiness and good fortune, the gossip began, and some became envious. In 1697, the first accusation came: A local man accused Grace of using a spell to kill his bull [3]. Grace sued for defamation, and it was settled. The following year, two more people accused Grace of witchcraft. First, a neighbor claimed his pigs and cotton were bewitched and destroyed. Another, Elizabeth Barnes, claimed that Grace transformed into a black cat and entered her home through a keyhole, then beat and whipped her, causing her to miscarry [5].

Over her lifetime, Grace would be accused over a dozen times. After her husband passed away in 1701 and she inherited their farm, she would be accused again. Elizabeth Hill accused her of assault in 1705, then a year later, she claimed that Grace bewitched her and caused her to have a miscarriage. This final accusation and pressure from Elizabeth Hill and her husband caused The Princess Anne County court to seek a jury to search Graces’ body and her home for evidence of witchcraft.

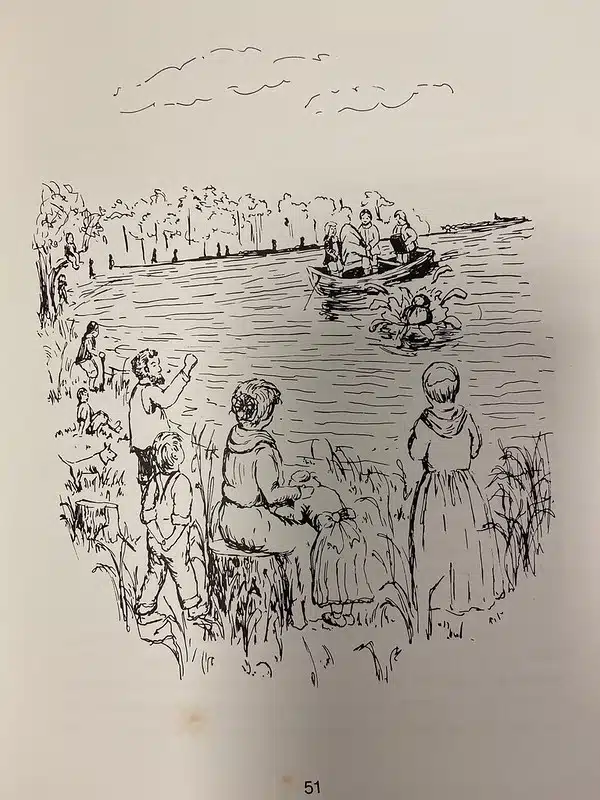

An all-women jury was assembled to inspect Graces’ naked body, and several older women, including Elizabeth Barnes, who accused her of turning into a cat, investigated her body. They concluded she had two “witches’ marks” and declared her a witch. When the church asked her to repent for being a witch, instead of confessing, she stated, “I be not a witch. I be a healer” and was sentenced to a “trial by ducking.”

With her right thumb bound to her left big toe and her left thumb to her right big toe, covered in a sack with a 13-pound Bible strapped to her neck, she was thrown into the river. If she was innocent, she would sink, showing her soul was pure. If she floated, it was a sign that she was a witch, and the water rejected her. Grace was able to free herself and swim to shore. She was declared guilty and spent nearly eight years in prison. When she was finally released, she returned to her farm and lived there until she passed away at 80.

1. Ideas About Original Sin (And A Very Misleading Book)

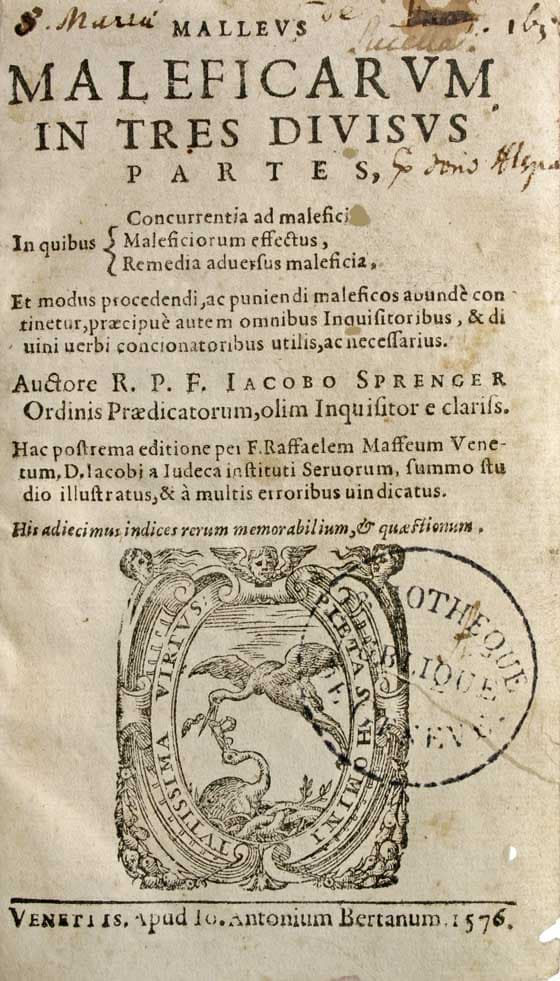

1. Ideas About Original Sin (And A Very Misleading Book)1486 Latin book The Malleus Maleficarum, or The Hammer of Witches, stated that witches were more commonly women because of women’s wicked nature and tendency to lie, lust, and have lesser intelligence [4]. Midwives were especially feared because of their wickedness in preventing conception or terminating a pregnancy and supposedly offering children to devils [4]. This position on women was only magnified in colonial times because of the religious teachings of the time, blaming Eve’s original sin for cursing all women to be more likely to be tempted by the devil since it was Eve who not only ate the fruit but convinced Adam to eat as well [5].

In today’s world, pregnancy and birth are often an exciting time for women, and we don’t usually assume we or our baby will die in the process. In colonial times, death was expected. It was widespread in childbirth, so common that women associated childbirth with death because of stillbirths or dying from labor complications or postpartum infections [5]. Childbirth was considered the woman’s sphere, and midwives, sometimes the only medical providers in an area, often gave laboring women herbs to help with labor pains or speed up delivery [5]. Midwives were respected but also faced scrutiny for challenging societal norms by having a job outside the home and feared for possessing knowledge of magic and power over life and death in a society where death was so ever-present [5].

Social activists Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English noted that witch hunts were correlated to men joining the medical profession. They support this correlation by the fact that an English licensing law was approved requiring formal education for women healers, and without a formal education, they could be charged as a witch by law [5]. Because of this, midwives and healers were targeted with accusations of witchcraft, especially if they could not heal their patients, save them from death, or if they were widowed, poor, or elderly [5]. Male healers saw women healers as competition, and by accusing women healers of witchcraft, they could remove them from the profession [5].

An example is Dr Philip Reade suing two women for gossiping about his treating a woman with swelling under her chin and apron [5]. He sued them for £100 (£18,000, or $21,800 in today’s money) and tore apart their reputations. He could continue his practice, but the women healers he accused were left without a job [5].

The midwives and woman healers of colonial times set an example for every woman after them. They showed that women could have control over their own lives, support themselves with an income, and be respected in the community, challenging the patriarchy of the time that expected women to heal and nurture in the home, subservient to their husbands and leadership of their colonies [5].

The tradition of delegitimizing women healers and midwives would only continue and has led to poor maternal outcomes for women to this day. By the mid 1800s medicine became professionalized, and by the beginning of the 1900s, midwives were only attending roughly half of all births in the U.S [6]. In 1915, Dr. Joseph DeLee, the head of obstetrics at Northwest University medical school and chairman of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago medical school, changed the view of birth as being a natural function of women, to a destructive process that must be taken care of in hospitals [6]. His interventions to “save women from the evils natural to labor” included sedatives, episiotomies, and forceps, which today are all known to cause harm [6]. DeLee was an influencer that led many other doctors to reduce midwives and label them as untrained and incompetent. He stated that the dangerous condition of pregnancy should only be cared for by highly trained medical specialists, and that the poor women who were often the clients of midwives, were needed by hospitals to train doctors in obstetrics [6].

By the 1930s the damage had been done to the reputation of midwives, and most midwives by that time were Black or poor white granny midwives working in the south. Between 1915 and 1929, the infant mortality rate skyrocketed by 41%, due to obstetrical interference in birth [6].

Thankfully, pregnancy and birth are starting to be viewed again as natural processes. For instance – hospital systems are beginning to recognize that interfering in labor is often not needed, unless there is an emergency. Instead of only recommending formula feeding, providers are recognizing the importance of breastfeeding, and many hospitals have lactation consultants to support those who choose to breastfeed [6]. The influential role of certified nurse-midwives in the 1960s introduced the concept of family-centered maternity care, which included keeping the baby in the mother’s room, encouraging breastfeeding, and even allowing fathers in the delivery room [6]. Today, there are many safe options for birth in hospitals, outpatient birth centers, and in a low-risk pregnancy, even at home.

This Halloween Season, we wanted to bring you these women’s stories who were midwives and healers, tried as witches. These women can be seen as role models for feminists today regarding personal agency for their careers, to speak their minds, stand up for what they believe, and threaten the status quo. Let’s remember them and continue challenging the patriarchy that tries to control our bodily autonomy and access to healthcare today.

[1] Blakemore, E. (2023, June 27). The mysterious enslaved woman who sparked Salem’s witch hunt. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/news/salem-witch-trials-first-accused-woman-slave

[2] Brooks, R. B. (2013, January 15). Margaret Jones: First person executed for witchcraft in Massachusetts. Retrieved from https://historyofmassachusetts.org/margaret-jones-first-person-executed-for-witchcraft-in-massachusetts/

[3] Grace Sherwood: The “Witch” of Pungo. (2023, July 28). Retrieved from https://salemwitchmuseum.com/2023/07/28/grace-sherwood-the-witch-of-pungo/

[4] Lewis, J. J. (2019, February 16). Malleus Maleficarum, the Medieval witch hunter book. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/malleus-maleficarum-witch-document-3530785

[5] Parker, J. C. (2018). Agents of the Devil?: Women, witchcraft, and medicine in early America [Master’s thesis, Appalachian State University]. UNCG University Libraries. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/f/Parker_Jewel_2018_Thesis.pdf

[6] Rooks, J. P. (2022, August). The history of midwifery. Retrieved from https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/health-info/history-of-midwifery/#:~:text=Obstetricians%20like%20DeLee%20and%20others,mainly%20poor%20women%E2%80%94were%20needed

[7] Schiff, S. (2015, November). Unraveling the many mysteries of Tituba, the star witness of the Salem Witch Trials. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unraveling-mysteries-tituba-salem-witch-trials-180956960/